£AN 2: Tim€ i$ Mon€y

5.5.2023

10:00 – 18:00

HKB Bern, VisKom & SFG BB

Write-up by Max Weinland

It is not warm,

but it could be warm.

Erich Fried

This symposium at the HKB Bern (initiated by Urs Lehni and the team of BA VisKom) was the first academic graphic design symposium, at least to my knowledge, that explicitly focused on the conditions of labor of graphic design. Neither visuality, portfolios, techniques, nor results of designing were addressed. Its inviting tagline was »How to talk about graphic design without talking about graphic design«. A nice subtraction: the main things left to talk about would be labor and value. Finally, a transdisciplinary symposium in the literal sense of transcending the circular discourse of the discipline!

I really enjoyed that there was no feeling of competition, no masturbation over prestige projects or fetish objects and very low levels of moralism, elitism and snobbery – something I thought was nearly impossible at a liberal arts university. Students and speakers were discussing economic questions, class relations (without necessarily using those exact terms), role models, social work, awards, the inevitable complicity and entanglement in capitalist relations and the role of design education in all of this. The range of topics discussed was quite wide and – despite the symposium running merely for a day – many attendees confirmed to me that this symposium was in fact an event, discussion-wise. While the day surely and expectably had its rather market-liberal moments – like when crowdfunding and entrepreneurialism where deliberately advertised as models for civil engagement while shrugging off public institutions and collective, political action – there was a sense of possibility and historical contingency that was quite strong.

In the morning, there were different workshops that students could sign up to. These workshops ran simultaneously and so the students and invited lecturers were able to focus on one topic more deeply. In the early afternoon, all the groups and some more visitors came together for a public presentation and discussion on the topics, wittily and expertly moderated by Massimiliano Audretsch. I can of course only describe my own workshop and our group presentation in more detail, but I want to try and give an account of what went on during the day.

In one workshop (Survival Skills), Florian Jakober, formerly of graphic design studio Afrika, talked about his moving away from designing and towards social projects like a food sharing cooperative (koop.cc). Sandro Alvarez-Hummel, of the crowdfunding platform wemakeit.ch, talked about fundraising for such self-initiated social projects. They talked about the historical development of the profession of the graphic designer. They apparently also referred to Viktor Papanek’s ambitious (and in my opinion misleading) claim that there are hardly any professions more harmful than that of the graphic designer, who advertises all of those destructive things invented by product designers as beautiful and desirable. I wish I could participate in a second iteration of that workshop to critically discuss these ideas. During their public presentation I had to go outside to answer the phone, so I can sadly not discuss their outcomes and attitudes in a fair manner. Talking to Florian Jakober in person about social responsibility issues and economic relations was great, though.

Another workshop was about associations and unions(!), a topic completely underserved in Germany’s graphic design/advertising field. A representative from the Swiss trade union Syndicom and two graphic designers, The Project Black, co-initiators of the Syndicom Manifesto, were there to talk about worker organization, union memberships, unemployment insurance and retirement plans. I would have signed up for that one, had I been there as a student. In the discussion afterwards, we voiced our common frustration about the unwillingness of a lot of designers to acknowledge that they are workers, like most other people, and that they are not above anyone. I recalled a line from Claudia Doms’ Letter to a Friend that basically said that she feels closer to her hairdresser than to these cool designer figures – a sentiment that I can only subscribe to.

Another interesting workshop musst have been that about Copyright & Copyleft, by intellectual-property-lawyer and graphic design collector Noa Bacchetta. It dealt with the rights of graphic designers to their works, the question of intellectual property in the age of sampling and memes and about possible alternatives like Copyleft.

In yet another important workshop and presentation, graphic designers Juliane Wolski, member of the Berner Design Stiftung and Aude Lehmann, co-head of the HKB VisKom Department and former member of the Eidgenössische Designkommission, talked about state funding for design projects and about design awards. A controversial topic, as the latter turned out to be, it was discussed wether design awards can be remodeled into something that doesn’t just become another currency in some cool corner of the field, or a mechanism to uphold the dominance of a few established studios. The participants later on presented their own ideas on how to remodel design awards, which led to a fruitful discussion. During the discussion, I talked about my experiences with awards in Germany, like the ADC or the now discontinued LEAD Awards, and how corrupt the judging processes are or have been. I don’t think that making capitalist reality look great – which is what most design and advertising is there for – should be awarded anyway. But awards have an important economic function for the industry and any sort of superficial moral criticism like that falls short of hitting the actual target: the capitalist mode of production that necessitates such award economies.

In my own little workshop (What is my work worth?) I sat down with five BA-students, among them Seba, who had completed an apprenticeship as a Polygraph before applying for University and thus had some experience in production labor they could share. All of the students wanted to know how to quantitatively evaluate labor – a difficult task for people working in or studying this »creative« field of graphic design, given that »creative« work is usually still being mystified as something that is not really work.

In the first half, we sat around comfortably on a sofa, talking about each one’s situation, outlook, expectations and experiences. I shared my own experiences as both an employee and a freelancer, my insights on why colleagues often hesitate to talk about money, what it might have to do with workplace culture and competitive thinking, the pitfalls of both employment and freelancing and the skills it takes in pretty much any job. We talked about work and overwork, frustrations, anxieties and the seeds of politics. We talked about feeling alone. Then we took a break.

In the second half of my workshop, we sat around a table and it got really concrete. I showed them estimates and invoices I had written (from real, recent commissions). I told them how to separate and evaluate the different processes within their work, how to properly assess their respective economic situations and what the real wage is.

The conversation then got us towards pretty dire outlooks – catastrophic climate change and the unfathomable wealth disparity and all that – towards which we ended on a high note: we can truly change things when we realize that we are codependent as workers and political people first, and graphic designers second (or third or even last).

Later on, in the public discussion, Seba made a powerful statement, expressing frustration about the romanticism that graphic design teachers often convey when it comes to economic issues, and how it is so hard to match teachers’ stories about the golden years of »small studio practice« in the late 1990s to early 2000s to todays economic reality. When even those teachers, who had just before dwelled in memories of that time, fully agreed and stated their own disillusionment, it felt like a solidary shift. We are in this together, after all.

I feel like this symposium was an important, necessary and exemplary opening of academic design discourse towards greater social and economic relations. I was also glad to not discover elements of design totality discourse – the unfortunate tendency to impatiently mystify everything from thinking about things to implementing policies on an institutional level as acts of design. This popular ideology expands the notion of design until it collapses over everything, making it unlikely for designers to see far more important aspects of things. It universalizes a very particular, limited view and thus firmly puts the designer and their vocabulary into the center of things, protecting them from having to deal with or articulate more ambitious and uncomfortable critiques, like that of current social relations and their entanglement and, in part, origins in capitalism. What most design workers do know very well, is their surroundings and power relations in the workplace and it is these issues that we need to tackle if we want to overcome academic elitism, anti-worker-resentment and naive »artist critiques« and improve conditions for everyone.

Finally, I have to say that it was the nicest, most collegial and critical design symposium I have witnessed and I hope to see more events like this come up. Also, thanks to Massimiliano Audretsch and Sophie Bunz for being such great hosts.

Design academia needs to get off of its high horse if it wants to become a force for change.

Design academia is asking almost the right questions.

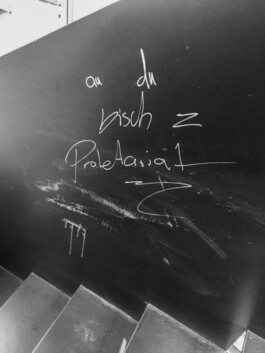

The question it doesn’t ask has a correct answer, written on a staircase wall at the HKB: »au du bisch z Proletariat.« (»You too are the proletariat.«)